Freeman Dyson in the report from the 2001 World Economic Forum defined the Precautionary Principle as "that if some course of action carries even a remote chance of irreparable damage to the ecology, then you shouldn’t do it, no matter how great the possible advantages of the action may be. You are not allowed to balance costs against benefits when deciding what to do."

Wired writer Kevin Kelly points out that the precautionary principle is effective for only one use—stopping technology. But every good produces harm somewhere, such as DDT, asbestos.

If certain technologies are only in hands of our enemies, suppressing them reduces our knowledge, increasing their danger.

Fears aren’t science.

No other political campaign has been so destructive to innovation, according to George Gilder.

Kelly posits a “proactionary principle,” emphasizing provisional assessment and constant correction, exactly what free markets do.

The epigraph to Adam Thierer’s (Mercatus Senior Fellow), book, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom is:

It is not the fruits of past success but the living in and for the future in which human intelligence proves itself. --F.A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (1960)

The precautionary principle insists on the permission question:

Must creators of new technologies seek the blessing of public officials before they develop and deploy their innovations?

Two conflicting attitudes are evident:

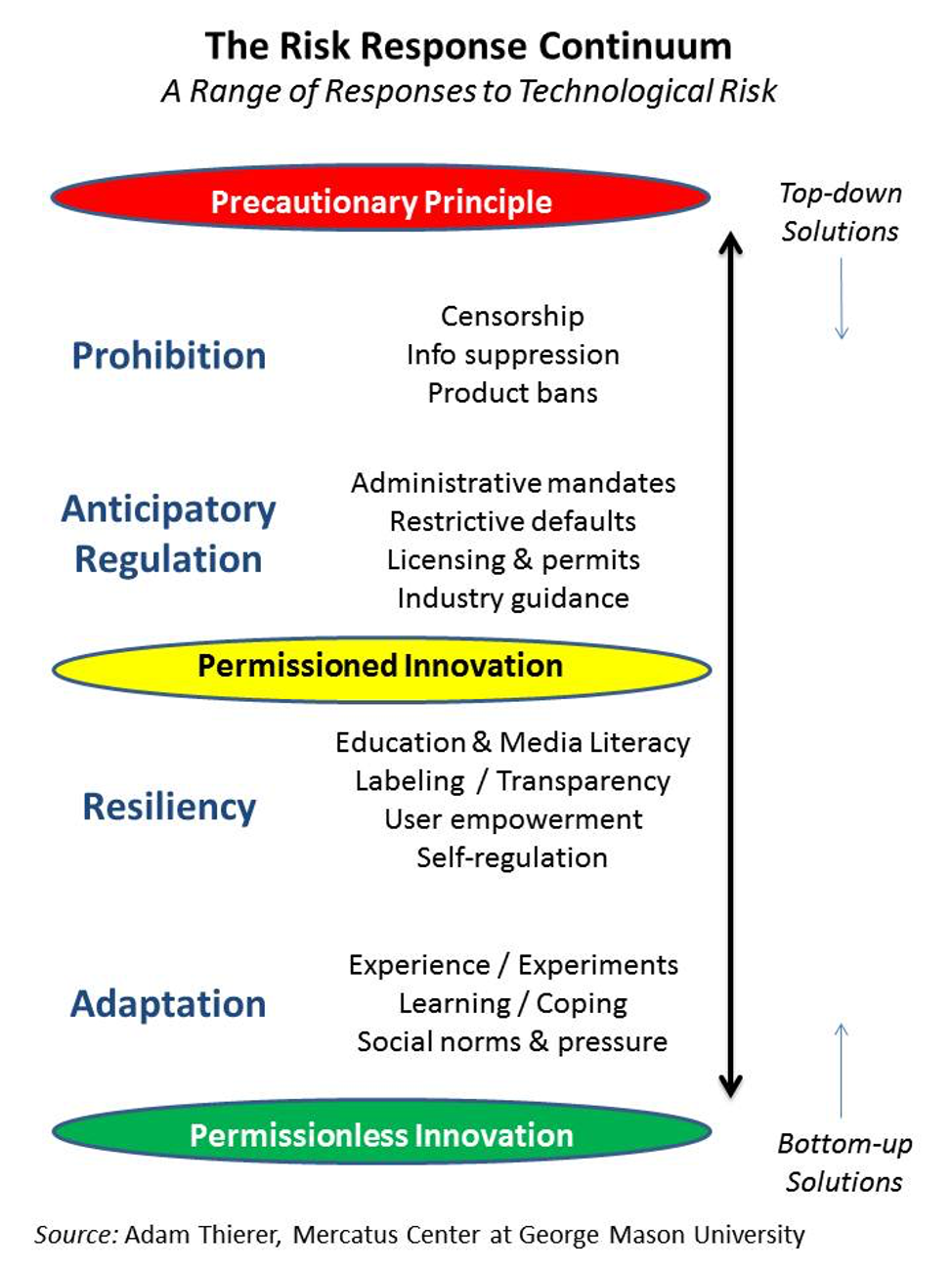

Precautionary principle: Innovation should be curtailed or disallowed until their developers can prove that they will not cause any harms to individuals, groups, specific entities, cultural norms, or various existing laws, norms, or traditions.

Permissionless innovation: experimentation with new tech and business models should generally be permitted by default. Not “Mother, May I.”

Fears of worst case scenarios affecting public policy means best-case scenarios will never come about. There are risks in misperceiving risks

FDA did halt 23andMe from marketing in 2013. But permissionless innovation is not about protecting any technology, sector, business, but rather for the benefit of citizens and consumers.

Policymakers should not impose prophylactic restrictions without clear evidence of actual harm, not merely hypothetical harm, such as was posited over net neutrality.

Vint Cerf, one of the fathers of the Internet, credits permissionless innovation for the economic benefits of the Net. Until 1989, commercial use of the Internet was prohibited, as government was unable to imagine the enormous benefits.

Dynamism vs. stasis is a constant battle. We are a conservative species, with built-in loss aversion and the negativity bias: the tendency to pay closer attention and give more weight to negative events, beliefs, and information than to positive events.

Technocrats seek to gain control over the future course of technological development, and their tool is the precautionary principle.

It’s failure that makes permissionless innovation such a powerful driver of positive change and prosperity. We can’t have trial without error.

If you can do nothing without knowing first how it will turn out, you cannot do anything at all.

There is also risk mismatch: fear-based tactics/threat scenarios can lead us to ignore quite serious risks because they’re overshadowed by unnecessary panics over nonproblems.

The most notable concerns from advocates of the precautionary principle are privacy, safety, and security.

But we ignore regulatory irrationality or regulatory ignorance. If consumers are ignorant, so is government. This is why Public Choice economics is known as government without romance.

Markets are more nimble than mandates. And markets pay for their mistakes. We are not skeptical of experts. We’re skeptical when they don’t pay a price for their errors.

Worst case scenarios don’t usually come about: we are resilient—anti-fragile.

In an 1890 Harvard Law Review article, Samuel D. Warren and Louis D. Brandeis wrote “The Right to Privacy,” which decried the spread of public photography. Since then:

Caller ID sparked a heated privacy debate in the 1990s

RFID likened to biblical threat, mark of the beast, Wired, 2006

Gmail hostility by privacy advocates

Wireless location-based services

After the panic, we almost always embrace the services that once violated our visceral sense of privacy.

The Law of Disruption: Technology changes exponentially, but social, economic, and legal systems change incrementally.

Skype proceeded without regard to US regulatory approvals and got a two-year head start.

Adam Thierer contrasts Legislate and Regulate vs. Educate and Empower. Markets are gradual, trial and error, and responsible for harm through torts, common law, and class-action lawsuits as protection (restitution-based, not permission-based).

Andy Grove posited: High tech runs three times faster than normal businesses. And the government runs three times slower than normal businesses. So we have a nine times gap!

“Despite his best intentions, the government planner will tend to live in the past, for only the past is sure and calculable.” George Gilder

Other Resources

Episode #87, Risk is Not a four-letter word.

Episode #184, Interview with Professor Thomas Hazlitt, author of The Political Spectrum, for examples of how government slowed innovation in our utilization of the spectrum.

Bonus Content is Available As Well

Did you know that each week after our live show, Ron and Ed take to the microphone for a bonus show? Typically, this bonus show is an extension of the live show topic (sometimes even with the same guest) and a few other pieces of news, current events, or things that have caught our attention.

Click the “FANATIC” image to learn more about pricing and member benefits.

Here are some of the topics and links Ron and Ed discussed during the bonus episode this past week:

More examples of subscriptions and how they might be the answer for traditional transaction based businesses that are currently being effected by COVID-19

Why global warming might reduce the number of viral breakouts

The viral TP epidemic and lessons to be learned