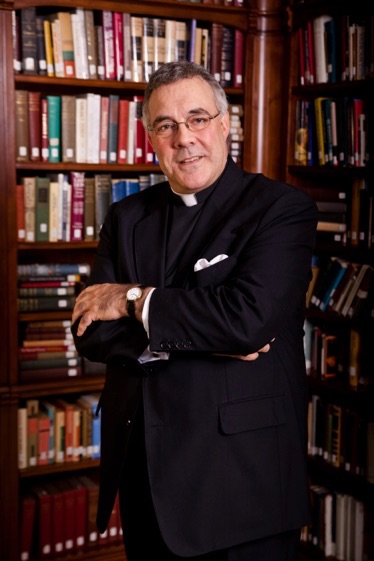

Ed and I were absolutely honored to interview Dr. Thomas Sowell, certainly one of the world's greatest living economists, on The Soul of Enterprise: Business in the Knowledge Economy. Dr. Sowell is currently Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. Sowell was born in North Carolina, but grew up in Harlem, New York. He dropped out of high school and served in the United States Marine Corps during the Korean War. He received a Bachelor's degree, graduating magna cum laude from Harvard University in 1958 and a Master's degree from Columbia University in 1959. In 1968, he earned his Doctorate in Economics from the University of Chicago.

Dr. Sowell has served on the faculties of several universities, including Cornell University and University of California, Los Angeles. He has also worked for think tanks such as the Urban Institute. Since 1980, he has worked at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. He writes from a conservative and classical liberal perspective, advocating free market economics and has written more than thirty books. He is a National Humanities Medal winner.

The new edition of his international best seller on economics, Basic Economics – 5th Edition (Basic Books, December 2015), was the focal point of our discussion.

Basic Economics is the best single volume primer on economics ever written. There are no graphs or equations, and the writing is clear, uncomplicated, eye-opening, and cogent. Ron has recommended this book to hundreds of people, most have thanked him profusely.

We discussed Dr. Sowell's early years as a Marxist, his definition of an economy and economics, early baseball tryout, the notion of a "fair" price, the illogic of the "trade deficit," his views on immigration, Thomas Pikkety's book and income inequality, and why there are only "non-economic values."

We also asked Dr. Sowell during the break what he thought of President Obama's recent policy on easing restrictions on Cuba. He was adamantly against it, and hopefully he will be writing on this topic for his syndicated column.

It's difficult to suggest one of Thomas Sowell's books over another. Be sure to read Basic Economics, 5th Edition, but if you want to venture beyond that (and you will), we've listed Dr. Sowell's books below, though not all of them. He's written two on late-talking children as well, which I hear are excellent.

Ron's favorites are: Knowledge and Decisions; A Conflict of Visions; and Intellectuals and Race.

Other Resources

Dr. Sowell's Wikipedia page.

Fred Barnes interview with Dr. Sowell.

Article by Jay Nordlinger, of National Review, on Thomas Sowell.

Follow Dr. Sowell's syndicated newspaper column on Twitter @sowellcolumn

Books by Thomas Sowell (partial list)

Say’s Law: An Historical Analysis, 1972

Classical Economics Reconsidered, 1974

Knowledge and Decisions, 1980

Markets and Minorities, 1981

Ethnic America: A History, 1981

The Economics and Politics of Race, 1983

Civil Rights: Rhetoric or Reality, 1984

Marxism: Philosophy and Economics, 1985

Education: Assumptions Versus History, 1986

A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles, 1987

Compassion Versus Guilt and Other Essays, 1987

Preferential Policies: An International Perspective, 1990

Inside American Education: The Decline, the Deception, the Dogmas, 1993

Race and Culture: A World View (Part I of a trilogy), 1994

The Vision of the Anointed: Self-Congratulation as a Basis for Social Policy, 1995

Knowledge and Decisions, 1996 (1980 original)

Migrations and Cultures: A World View (Part II of a trilogy), 1996

Conquests and Cultures: An International History (Part III of a trilogy), 1998

The Quest for Cosmic Justice, 1999

A Personal Odyssey, 2000

Basic Economics: A Citizen’s Guide to the Economy, 2004

Applied Economics: Thinking Beyond Stage One, 2004

Black Rednecks and White Liberals, 2005

Every Wonder Why (collection of columns), 2006

A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles, revised and expanded 2007

A Man of Letters, 2007

The Housing Boom and Bust, 2009

Intellectuals and Society, 2009

Applied Economics: Thinking Beyond Stage One, Revised and Enlarged Edition, 2009

Dismantling America (collection of columns), 2010

The Thomas Sowell Reader (collection of columns, essays, etc.), 2011

“Trickle Down” Theory and “Tax Cuts for the Rich,” (essay), 2012

Intellectuals and Race, 2013

Basic Economics: A Citizens Guide to the Economy, 5th Edition, 2015