Ed’s Topics

Bitcoin

Reaches high of $1,300, surpassing gold. Market cap is over $21 billion.

United Airlines

Possible new slogans:

“Not enough seating, prepare for a beating”

“Drag and Drop”

“We put the hospital in hospitality”

“Board as a doctor, leave as a patient”

“Our prices can't be beaten, but our passengers can”

“We have First Class, Business Class and No Class”

“We treat you like we treat your luggage”

“We beat the customer, not the competition”

“And you thought leg room was an issue”

“Where voluntary is mandatory”

“Fight or flight - We decide”

“Now offering one free carry off”

“Beating random customers since 2017”

“If our staff needs a seat, we’ll drag you out by your feet”

“A bloody good airline”

Air travel is not a right, but a privilege, governed by “The contract of carriage,” which is the same for all airlines.

If a flight is overbooked, Department of Transportation rules say for involuntary removals:

The airline must ask for volunteers

They must spell out your rights

They must rebook you, and pay if significantly delayed ($1350 maximum if more than 2 hours delayed, 4 hours for international)

Must cut a check on-site if you ask

If you voluntarily give up your seat, you’re on your own

If they bump you for any other reason (weather, flight cancelled, change to a smaller plane, weight-and-balance issues, etc.) these protections don’t apply.

Supersonic Jets?

Boom Technology wants to take you from New York to London in three hours.

Robots and Job Loss

Ron’s Topics

File Under: No Such Thing as a Commodity

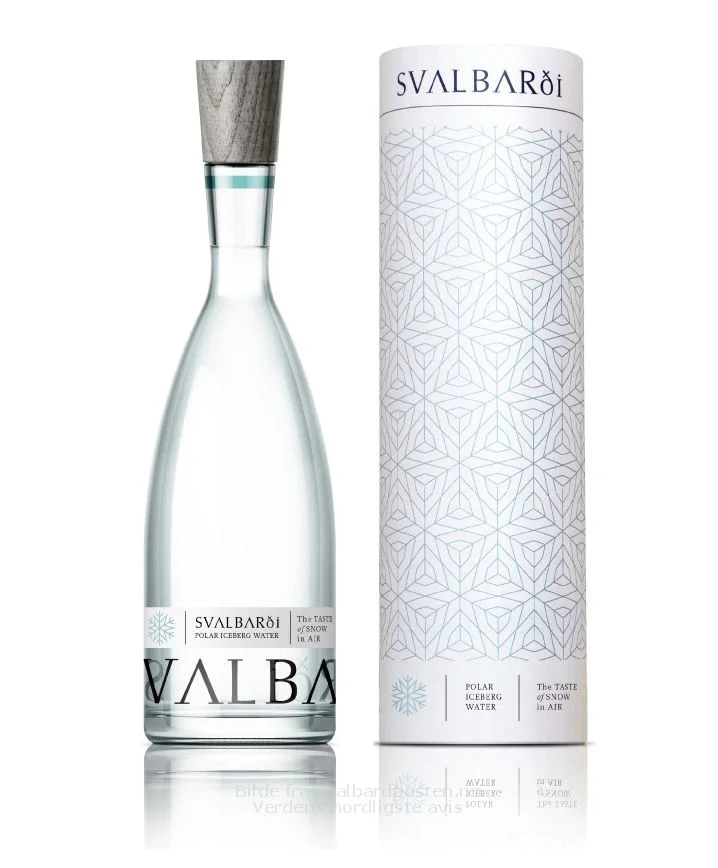

“Liquid gold,” The Economist, March 25, 2017

Water brand Svalbardi sells for $99!

The bottled water industry has grown for 9% per year, for years, reaching a market of $147 billion. “Premiumisation” brands are the fastest growing (defined as priced at greater than $1.30 a litre). Flavored water is 4% of the volume, and 15% of the revenue.

Bottled water consumption surpassed sugary soft drinks in the USA in 2016.

Big Tooth

NPR Podcast, Planet Money: The Economy Explained: Episode 759: What’s It Worth To You? March 17, 2017

In the Obama White House there was a Council of Economic Advisors meeting, and they were all waiting for Jack Lew, the US Treasury Secretary to arrive.

One of the economists, Betsy Stevenon, asked the other economists: What’s the tooth fairy paying these days?

Turns out that Delta Dental has conducted a poll for the last 20 years, and $4.66 is the average paid out for a lost tooth. (Ed is cheap. His kids get $10 for the first tooth and $1 thereafter, an average of $1.46 a tooth.)

The astounding thing is that the growth has been over 10% per year!

Economists use “Income Elasticity of Demand” to explain spending. In other words, if you earn 10% more income, do you spend 10% more on each category of spending?

The theory is parents love to splurge on their kids, especially if they are only children.

Facile Externalities?

“Friction Lovers,” The Economist, April 1, 2017

Too much of a good thing can be bad, like travel leading to congestion.

Academic economists in Scandinavian countries term this situation a “Facile externality”: where less efficiency would actually be more efficient.

They claim that innovations which eliminate too much hassle for consumers could inflict a net harm on society.

Jerry Seinfeld: “I love Amazon 1-click ordering. Because if it takes two clicks, I don’t even want it anymore.”

The foregone benefits of hassle (slygge in Danish):

Frictionlessness encourages bad habits

Dominoes zero-click pizza buying, open app and in 10 seconds it orders your pizza

Three out of five Britons say spend they more with the wave of plastic than cash

IKEA effect: people place extra value when devote own labor.

Market can’t solve this problem on it’s own, according to Danilov P. Rossi of DONUT, the UN’s Don’t Nudge—Tell office.

Only government can properly defend the cause of inefficiency.

The Economist magazine will lead by example. From now on a paper knife will be needed in which to separate the pages of your copy.

Isn’t this just a version of the labor theory of value?

Robot or Human Competition for Jobs?

“In Defense of Robots,” by Robert D. Atkinson, National Review, April 17, 2017

Atkinson is president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

There was a time in America when nearly all sectors—journalists, businesses, academics, etc.—advocated technologically powered productivity growth. Think Walt Disney.

Even socialists. Jack London said:

“Let us not destroy these wonderful machines that produce efficiently and cheaply. Let us control them. Let us profit by their efficiency and cheapness. Let us run them by ourselves. That, gentlemen, is socialism.”

Now theirs an inordinate fear of robots taking most of our jobs, leading Atkinson to coin this phenomenon Robophobia.

The three noteworthy studies predicting job losses:

Oxford: 47% jobs eliminated 20 years

McKinsey Global Institute: 45% jobs loss

PWC: 38% job losses by 2030

Atkinson demolishes these studies for faulty methodology.

It’s predicted, for example, that Long-haul truckers stand to lose 3.8 million jobs. But are these “great jobs”? Truckers have a seven times higher injury rate, and rank in the top five in suicide rates, earning an average annual income of $40,260, which is 17% below the national median.

Autonomous vehicles could save more than $1 trillion, and tens-of-thousands of lives. Do these benefits outweighs the costs imposed on truck drivers? Some good switch to becoming a truck mechanic, who make on average 15% more than drivers.

A lot of these fears suffer from the lump-of-labor fallacy, the idea that there are only so many jobs in the economy.

But there has always been a negative, not positive, relationship between productivity growth and unemployment. In other words, higher productivity growth meant lower unemployment.

Atkinson is against the Universal Basic Income, which he believes will lead to the very thing robophobes warn us technology will bring about: large-scale unemployment. He advocates tax-deferred Lifelong Learning Accounts, similar to the 401(k) retirement accounts.

Economist Donald Boudreaux recently wrote “Robots Substitute for Jobs, Not Human Creativity,” April 26, 2017, on the Foundation for Economic Education website.

He argues what’s more human-like than humans? From the 1950s, the USA workforce increased 160%, from 62 million to 160 million.

Yet the unemployment rate in 1950 was 5.3%; today it’s 4.5%. The labor force participation is 63% today but was 59.2% in 1950.

Believing robots take jobs is based on an incorrect presumption: that the number of productive tasks we can perform for each other is limited.

Boudreaux believes that number is practically unlimited.

So do we. As Ed added, "If your job gets taken over by a robot, it probably sucks!"