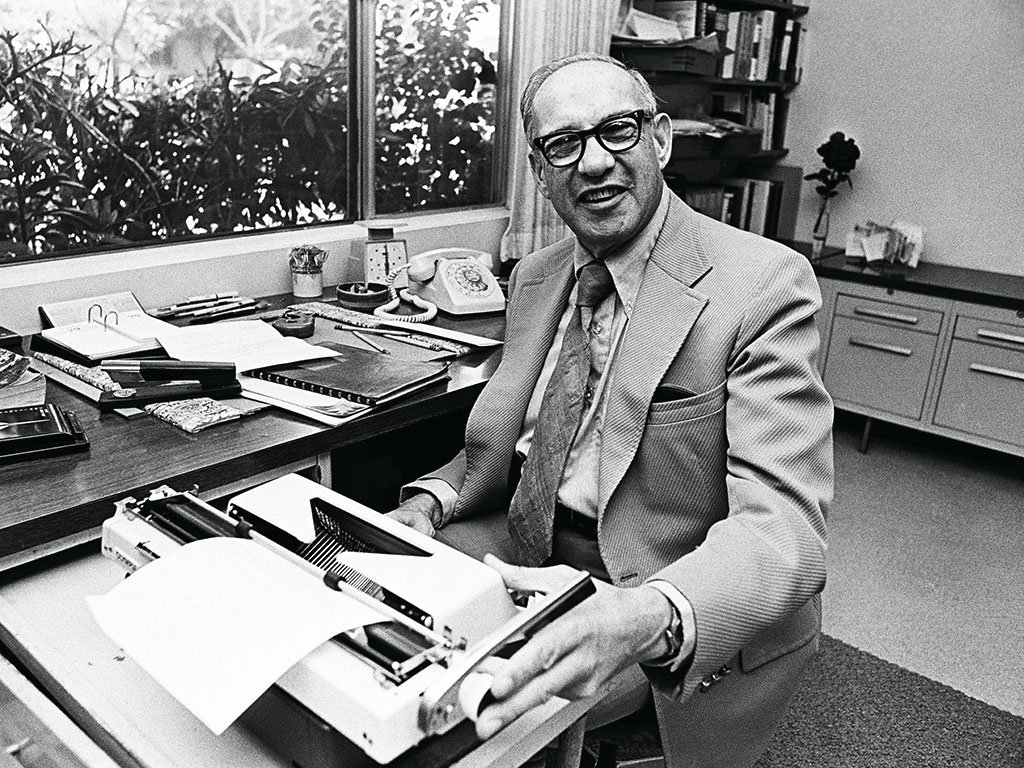

Peter F. Drucker is one of the truly serious thinkers the management consultant industry can point to with justifiable pride. Even though Drucker passed away November 11, 2005, at age 95, it does not mark the beginning of the end, but the end of the beginning, since he has left such a rich legacy. Along with the economics profession, Drucker alone is responsible for introducing, and being among the first to recognize, the knowledge worker and knowledge economy to the business world. Join Ron and Ed as they discuss the ideas, writings, thinking and influence of the most seminal management thinker of our times.

Peter Drucker is often invoked as saying, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” Yet, you cannot find this as a direct quote of Drucker’s. In our research looking for this quote, I found the following:

Reports and procedures should be the tool of the man who fills them out. They must never themselves become the measure of his performance. A man must never be judged by the quality of the production forms he fills out – unless he be the clerk in change of these forms.

He must always be judged by his production performance. And the only way to make sure of this it by have him fill out no forms, make no reports, expect those he need himself to achieve performance. – Peter Ferdinand Drucker, The Practice of Management, 1954, page 135.

Someone once wrote that you should read Drucker just to learn how he thinks.

Nowhere is that more true than this gem of a book: Technology, Management, and Society. A collection of 12 essays, dating from 1957 to 1969, which are so evocative all we can say is we are still grappling with the issues Drucker was so prescient in foreseeing over 50 years ago.

The essays are best summed up by Drucker himself, "…they stress constantly the purpose of management, which is not to be efficient but to be productive, for the human being, for economy, for society."

Drucker discusses the vital role of risk and profit in enterprise, as well as the brilliant observation that of all the institutions in society (family, church, government, professions, unions, not-for-profits, etc.) only the business enterprise is designed to create change:

Indeed, in the business enterprise we have the first institution which is designed to produce change. All human institutions since the dawn of prehistory or earlier had always been designed to prevent change—all of them: family, government, church, army.

Change has always been a catastrophic threat to human security. But in the business enterprise we have an institution that is designed to create change. It means that every business, to survive, must strive to innovate.

We can only provide a few examples of Drucker’s thinking, which do not do this little book justice. Here are some of our favorites:

But it should be said that in human institutions, such as business enterprise, measurements, strictly speaking, do not and cannot exist. It is the definition of a measurement that it be impersonal and objective, that is, extraneous to the event measured. A child’s growth is not dependent on the yardstick or influenced by being recorded.

But any measurement in a business enterprise determines action—both on the part of the measurer and the measured—and thereby directs, limits, and causes behavior and performance of the enterprise. Measurement in the enterprise is always motivation, that is, moral force, as much as it is ratio cognoscendi.

This is another way of expressing [Ed] Kless’ Law: All measurements are judgments.

On youth, Drucker wrote this, "The young are always in the right, because time is on their side. And that means we have to change."

Executives who believe they can change one aspect of a company without affecting others are ignoring the reality of a firm being an interdependent system. Drucker explained the phenomenon this way:

There is one fundamental insight underlying all management science. It is that the business enterprise is a system of the highest order: a system whose parts are human beings contributing voluntarily of their knowledge, skill and dedication to a joint venture. And one thing characterizes all genuine systems, whether they be mechanical like the control of a missile, biological like a tree, or social like the business enterprise: it is interdependence.

The whole of a system is not necessarily improved if one particular function or part is improved or made more efficient. In fact, the system may well be damaged thereby, or even destroyed. In some cases the best way to strengthen the system may be to weaken a part—to make it less precise or less efficient. For what matters in any system is the performance of the whole; this is the result of growth and of dynamic balance, adjustment, and integration, rather than of mere technical efficiency.

This seems to be lost on advocates of Lean Six Sigma, whether in professional knowledge firms or factories.

There’s also an excellent discussion of why knowledge workers are different than manual workers, and why this requires leaders to change their thinking.

Our only quibble is Drucker gives far too much credit to Frederick Taylor, who recent scholarship has determined was a fraud.

Peter Drucker on Business Models

One of Peter Drucker’s (1909–2005) many articles published in the Harvard Business Review (September-October 1994) was entitled “The Theory of the Business,” which laid out what he considered to be the essential elements executives would have to define in order to create wealth:

Not in a very long time—not, perhaps, since the late 1940s or early 1950s—have there been as many new major management techniques as there are today: downsizing, outsourcing, total quality management, economic value analysis, benchmarking, reengineering.

Each is a powerful tool. But, with the exceptions of outsourcing and reengineering, these tools are designed primarily to do differently what is already being done. They are “how to do” tools.

Yet “what to do” is increasingly becoming the central challenge facing managements, especially those of big companies that have enjoyed long-term success.

What accounts for this apparent paradox? The assumptions on which the organization has been built and is being run no longer fit reality. These are the assumptions that shape any organization’s behavior, dictate its decisions about what to do and what not to do, and define what the organization considers meaningful results.

These assumptions are about markets. They are about identifying customers and competitors, their values and behavior. They are about technology and its dynamics, about a company’s strengths and weaknesses. These assumptions are about what a company gets paid for.

They are what I call a company’s theory of the business.

In fact, what underlies the current malaise of so many large and successful organizations worldwide is that their theory of the business no longer works.

It usually takes years of hard work, thinking, and experimenting to reach a clear, consistent, and valid theory of the business. Yet to be successful, every organization must work one out.

What are the specifications of a valid theory of the business? There are four:

The assumptions about environment, mission, and core competencies must fit reality.

The assumptions in all three areas have to fit one another.

The theory of the business must be known and understood throughout the organization.

The theory of the business has to be tested constantly. It is not graven on tablets of stone. It is a hypothesis. And so, built into the theory of the business must be the ability to change itself.

Peter Drucker’s autobiography: Adventures of a Bystander, 1978, 1994

“I realized that I, at least, do not learn from mistakes. I have to learn from success.”

Socrates wasn’t a teacher, but a “pedagogue”—a guide to the learner.

The Socratic method isn’t a teaching method, it’s a learning method. For the teacher, the passion is inside him; for the pedagogue, the passion is inside the student.

A Functioning Society: Selections from Sixty-Five Years of Writing on Community, Society, and Polity, 2003

More of Drucker’s books deal with community, society and polity than management.

Marxism was the God that failed. “I once, in 1932, heard Hitler say in a public speech:

‘We don’t want higher bread prices; we don’t want lower bread prices; we want national-socialist bread prices.’ And 5,000 people in the audience cheered wildly.”

He coined the term re-privatization, from which Margaret Thatcher derived her policies of privatization.

The only successful policy of the Megastate is avoidance of World War III.

We no longer expect results from government. Only two things effectively: wage war and inflate the currency.

One thing red-tape is good for: to bundle up yesterday in neat packages.

“In the knowledge organization every knowledge worker is an “executive.” The number of people who have to be effective for modern organization to perform is therefore very large and rapidly growing. The well-being of our entire society depends increasingly on the ability of these large numbers of knowledge workers to be effective in a true organization. And so, largely, do the achievement and satisfaction of the knowledge worker.

To speak of “social responsibility of business assumes that responsibility and irresponsibility are a problem for business alone. Clearly, however, they are central problems for all organizations. The least responsible org today is not business, it’s universities.”

“Organizations don’t act socially responsible when concern themselves with social problems outside of their own sphere of competence and action. They act the most responsibly when they convert public need into their own achievements.”

“We need to what performance means. We need to be able to measure, or at least to judge, the discharge of its responsibility by an institution and the competence of its management….justifies their existence and power. Everything beyond is usurpation.”

“Knowledge workers cannot be supervised effectively. Unless they know more about their specialty than anybody else in the organization they are basically useless.”

Harvard Business Review Article, 1991

“Professional management hasn’t earned an ROI equal to its cost of capital. The raiders thus performed a needed function. Old proverb: If there are no grave diggers, one needs vultures.”

German and Japanese management don’t “balance” anything. Rather, they optimize the wealth-producing capacity of the enterprise (market standing, innovation, productivity, people and their development).

In his book The Landmarks of Tomorrow, 1957 is where Drukcer first used the term knowledge economy, and knowledge worker.

From Management Challenges for the 21st Century, 1991: The most important contribution management needs to make in the twenty-first century is to increase the productivity of knowledge work and the KW.

Knowledge work is unisex, equally well by both sexes. Corporations need knowledge workers more than they need them. Ultimately, knowledge workers are volunteers. Knowledge workers are more loyal to their profession than any organization.

Profits Come From Risk

Drucker’s three types of risks:

The risk a business could afford to take

The risk a business could not afford to take

The risk a business could not afford not to take

The Effective Executive in Action, 2006

This was the last book he published before passing away.

It details the five practices of the effective executive:

Managing your time;

Focusing your efforts on making contributions;

Making your strengths productive;

Concentrating your efforts on those tasks that are most important to contributions; and

Making effective decisions.

“An organization that is not capable of perpetuating itself has failed. It has to renew its human capital.”

“Strong people always have strong weaknesses too. Performance can only be built on strengths.”

“Character and integrity by themselves do not accomplish anything but their absence faults everything else.”

"Are you a reader or a listener? Trial lawyers are both."

“Good executives focus on opportunities rather than problems. Problem solving does not produce results (reverts to status quo). Exploiting opportunities produces results…”

“A decision is a judgment—a choice between alternatives. Rarely a choice between right and wrong. It is at best a choice between ‘almost right’ and ‘probably wrong.’ Untested hypotheses are the starting point. One does not argue with them; one tests them.”

“There’s too much about leadership and not enough on effectiveness. The only thing you can say about a leader is somebody who has followers. The most charismatic leaders of the last century were Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and Mussolini. They were misleaders.”

“I have yet to see a knowledge workers who couldn’t consign one-fourth of the demands on his time to the wastepaper basket without anybody’s noticing.”

There’s no such thing as business ethics

It is common today to speak of “medical ethics,” “bio ethics,” “accounting ethics,” and so forth. Yet some thinkers deny there are different ethical theories for these various functions.

In his 1981 article in The Public Interest, “What is Business Ethics”?, management thinker Peter Drucker challenges the concept of a separate ethics for business:

If “business ethics” continues to be “casuistry” its speedy demise in a cloud of illegitimacy can be confidently predicted. Clearly this is the approach “business ethics” today is taking. Its very origin is politics rather than in ethics. It expresses a belief that the responsibility which business and the business executive have, precisely because they have social impact, must determine ethics––and this is a political rather than an ethical imperative.

What difference does it make if a certain act or behavior takes place in a “business,” in a “non-profit organization,” or outside any organization at all? The answer is clear: None at all.

Clearly, one major element of the peculiar stew that goes by the name of “business ethics” is plain old-fashioned hostility to business and to economic activity altogether––one of the oldest of American traditions and perhaps the only still-potent ingredient in the Puritan heritage. There is no warrant in any ethics to consider one major sphere of activity as having its own ethical problems, let alone its own “ethics.” “Business” or “economic activity” may have special political or legal dimensions as in “business and government”..., or as in the antitrust laws. And “business ethics” may be good for politics and good electioneering. But that is all. For ethics deals with the right actions of individuals. And then it surely makes no difference whether the setting is a community hospital, with the actors a nursing supervisor and the “consumer” a patient, or whether the setting is National Universal General Corporation, the actors a quality control manager, and the consumer the buyer of a bicycle.

Altogether, “business ethics” might well be called “ethical chic” rather than ethics––and indeed might be considered more a media event than philosophy or morals (Drucker, 1981: 22-23; 31; 33-35).

Other Drucker Books

Drucker’s Lost Art of Management, Joseph A. Maciariello, 2011. This book details Drucker’s calling management a “liberal art,” and linking it to the humanities disciplines.

A Class with Drucker, William A. Cohen, 2007

Drucker on Marketing, 2012

The Practical Drucker, William A. Cohen, 2014

People complained Drucker didn’t tell them “what to do” or “how to do.” Rather, he asked questions.

This book details 40 important concepts on:

People

Management

Marketing and Innovation

Organization

Peter Drucker: Shaping the Managerial Mind, by John E. Flaherty;

The Definitive Drucker, by Elizabeth Haas Edersheim

The World According to Peter Drucker, Jack Beatty

Disagreements with Drucker

He gave Frederick Taylor too much credit.

He believed CEO pay was too high.

He did refer to people as assets [but also volunteers].

He believed time is the executive’s scarcest and most precious resource, and organizations are inherently time wasters. We believe time is a constraint, not a resource.